Discussing gender equality can be difficult in professional environments. Many women prefer to avoid this topic altogether, because complaining about inequality can be seen as career suicide. Women who rock the boat are often perceived as whingers, weak, and unsuitable for leadership positions.

Yet study after study supports the fact that women are still subject to bias in the workplace. This presents unique challenges generally not recognised by men.

Career opportunities

The Thomas Reuters Foundation surveyed almost 10,000 women from 19 of the G20 countriesabout the challenges they face in the workplace. One of the 5 recurring themes to emerge from this was that women are provided with fewer opportunities for growth than men. Out of all the Australian women surveyed, 45% stated that in their experience men have better career opportunities than women. This study is backed by research undertaken by the Australian Government’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency, whose 2016 report shows women hold only:

- 2% of chair positions

- 6% of directorships

- 4% of CEO roles

- 4% of key management personnel positions in Agency reporting organisations.

These figures show an underrepresentation of women in leadership roles, as almost half the Australian workforce (46.2%) are women.

So why is this? Research out of Stanford University suggests it has a lot to do with unconscious gender biases, which assign certain attributes to people based on their gender. Women are more likely to be described as “supportive”, “collaborative” and “helpful” in performance reviews, while men are more likely to have words like “drive”, “transform”, “innovate” and “tackle” included in their reviews. It’s no wonder that when the selection criteria for a promotion requires someone who is driven and innovative, it’s a man who is most often given the opportunity – regardless of which gender is in charge of hiring decisions.

Support in the home

A study of executive women and men, Leaders in a Global Economy, surveyed 1,192 executives from 10 participating countries, with a roughly even gender split. Of the respondents, approximately 75% of the men surveyed reported having a wife or spouse who did not work. Women, however, reported the opposite, with approximately 75% of them reporting having a husband or spouse who also worked full-time. To quote journalist Annabelle Crabb: “The men got wives. And the women didn’t.”

In isolation, you could argue that there’s no way to understand how those families split domestic, unpaid work between them. This study, luckily, went a step further and asked exactly that. The executives who had children were asked who takes more responsibility for making childcare arrangements. The response showed a strong divide, with 57% of women answering “I do”. In stark contrast, only 1% of men gave the same answer.

The value of having a spouse at home to take care of running the household cannot be underestimated. The idea of having ‘work-life balance’ is also something uniquely challenging for women due to the current social structure Australia stubbornly adheres to, which ascribes caregiving duties to women and breadwinning duties to men. As Quentin Bryce famously said: “[Women] can have it all, but not all at the same time.”

Being accepted as effective leaders

Australia is lagging in closing the gender gap, according to the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap report. Ranking 46th globally, notable sub-indexes where we underperformed include Economic Participation and Opportunity (42nd), Health and Survival (72nd), and, importantly, Political Empowerment (61st).

With so few representatives in political positions of power, is it any wonder there is still bias surrounding women’s ability to lead in the workplace?

An American study out of the Pew Research Centre examined women and leadership, and the perceptions surrounding their abilities. Surprisingly (or perhaps not so surprisingly), the majority of Americans feel women are every bit as capable at leading in business or politics as men are. They are, in fact, perceived as being more honest and ethical, better at being fair and better at mentoring employees.

Yet in spite of this, the number of women actually in those leadership positions was shockingly low. The study delved into this as well, and seems to suggest that though we believe women can be as good as men, we tend to expect them not to be. This creates a situation where, in order to be seen as equal to a man of similar standing, women must actually do more to prove themselves. Even when a woman’s efforts do go above and beyond those of a man, they are unlikely to reap the benefits; when male executives speak up among their peers, those peers would give him 10% higher ratings on his competence. When a female executive speaks up, her ratings were 14% lower.

How can we start to address these issues in the workplace?

Recognising factors that hold women back from excelling in management is only a small part of tackling gender inequality. If organisations are serious about furthering diversity in their workplaces – and taking advantage of the many skilled and talented women in Australia – then real, actionable steps need to be put in place.

Many companies are actively trying to do better. Google, Facebook and Microsoft have all amped up their efforts to create inclusive workspaces. Google, for example, empowers their employees to identify their unconscious biases through training and workshops, and have made resources available publicly through re:Work with Google. They also recognised that men are more likely to self-nominate for promotions than women, a trend that repeats in almost every industry and workplace. This has led them to explore other approaches to encouraging applications.

Research tells us that when women are active and equal in the workforce, everyone benefits. Business outcomes are improved, economies are stronger, and living conditions improve for entire communities. So why, then, do organisations so strongly avoid discussing inequality?

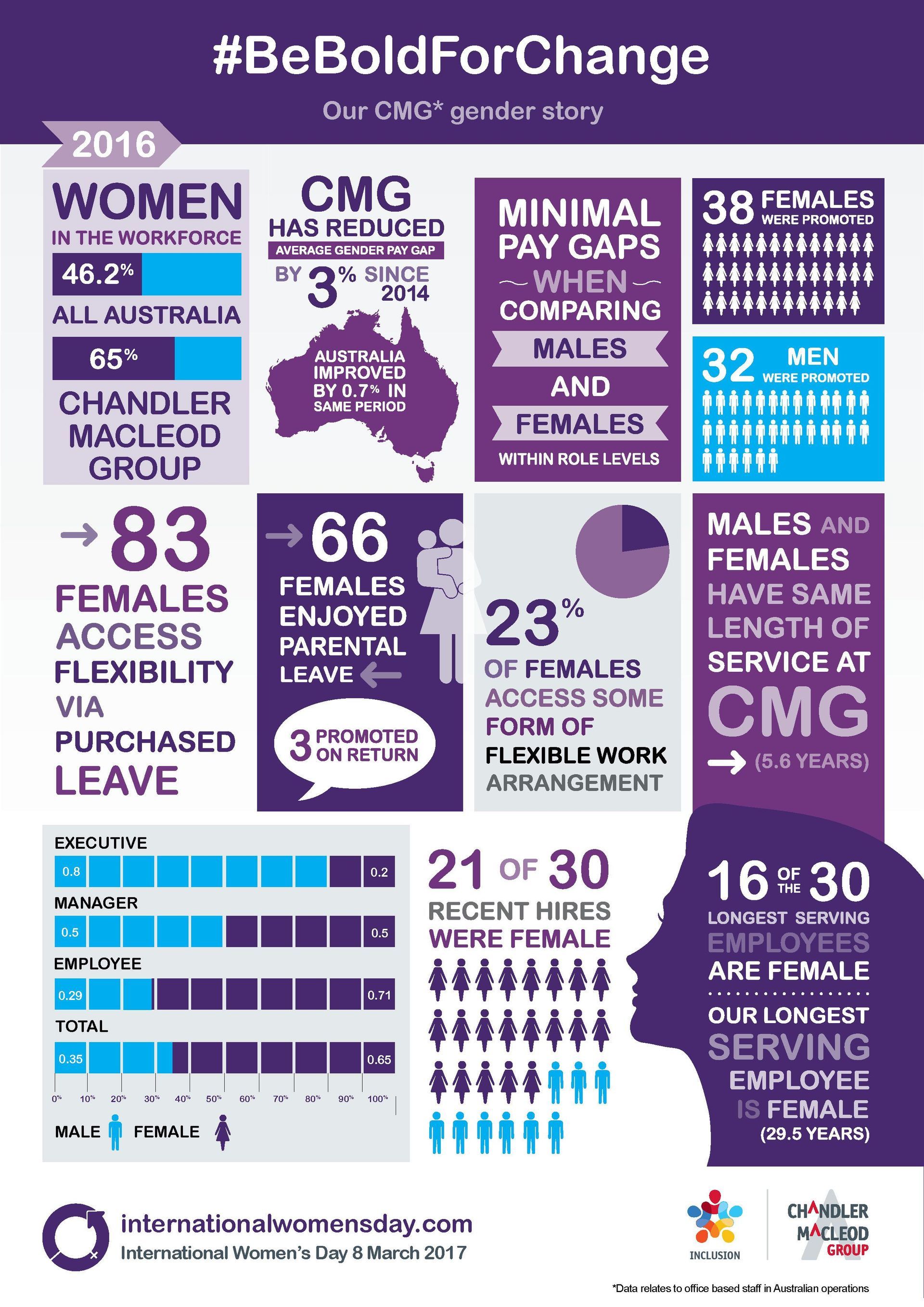

- 65% of our workforce are female, compared to 46.2% of the total workforce in Australia

- Since 2014, CMG has reduced the average gender pay gap by 3%. The Australian average over the same period was 0.7%

- In the last year, 38 women were promoted, whereas 32 men were promoted

- 83 of our female staff accessed flexibility via purchased leave

- 66 women enjoyed parental leave, with 3 being promoted on their return

- 23% of our female staff access a form of flexible working arrangement

- Males and females have the same average length of service at CMG – 5.6 years

- 21/30 of our most recent hires were female

- 16 of the 30 longest serving employees at CMG are female

- Our longest serving employee is female (29.5 years)

This isn’t a pat on the back, CMG as well as Australia, still has a long way to go before we can say there is real equality in our workforce. But we are proud of the efforts and achievements of both our male and female staff, in making our workplace a more diverse, equal, safe, and happy place.